Every month, I write and shoot a short documentary based on a single word. The One Word for this month is HOME.

I highly recommend you watch this month’s word, but you can also read it below.

It’s springtime in Toronto. The city has awakened from its icy sleep. Horns blast, bare limbs unfurl from puffy coats, and sometimes I see ghosts in the windows.

Everything is on the move.

I crave the sun and the outside, but no matter where I venture or what I’m doing, no matter the traffic — brutal and relentless and glacier — after a long day, I cannot wait to go home.

Old English - hām - House with land

I ended the last One Word, Dada, by promising my daughter I’ll always be there when she’s ready to return home. But what do I mean when I say home?

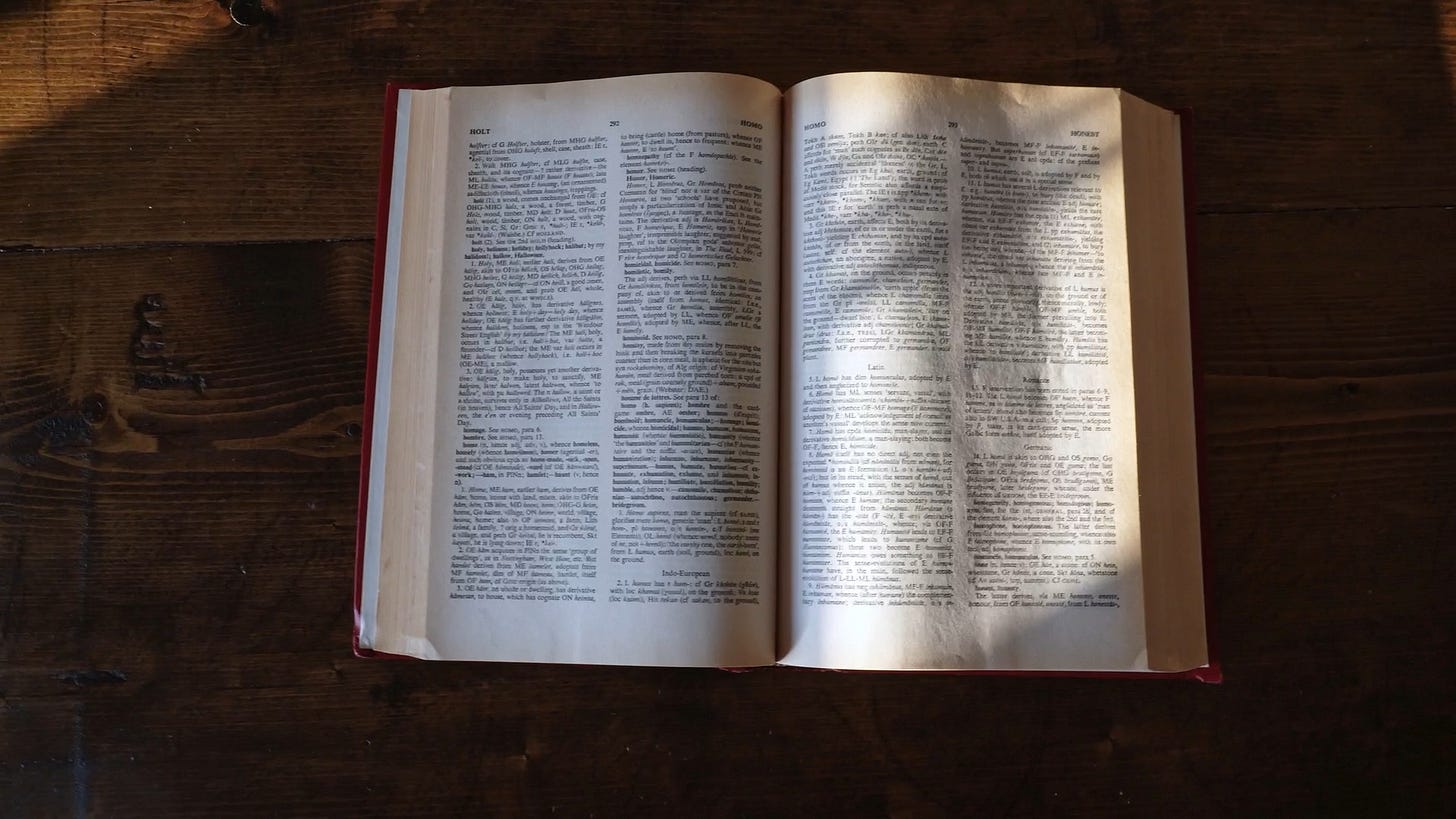

One of my most treasured possessions is a book, Origins by Eric Partridge. I start each One Word by following his journey back through the lineages and etymologies for a clue, a forgotten artifact of meaning. Home was no different.

Partridge discovered three distinct meanings for the word home, and the first is an Old English word, hām, which means house with land.

No goal in my life has been more pervasive and all-consuming than the quest for a house with land.

When my parents were my age, they succeeded in this quest. They bought an acre and a half in Aiken, South Carolina and built a home. This was my childhood, a Canadian living in the USA.

I remember crunchy beds of pine needles in the yard and that I rarely entered the house from the front door. Having moved from a small duplex in Toronto, the living room felt like a royal chamber.

We had a backyard with a pool, a deck, and a den above the garage. Our neighbours were friendly and forthcoming in that classical American way.

All of this exists for me now as memory spooled on videotape. The Aiken home left an impression, indelible, like a dimple thumbed into my cheek. It’s become the origin of my quest for a house with land.

But in Toronto, the cost of housing ballooned over the pandemic, and that once affordable dream feels out of reach.

At 36 years old, I cannot provide my daughter what my parents provided me, and I’ve had to accept the fact that what my parents had, I may never have.

To afford the modest town home we’re in now, my wife and I had to get a mortgage with her sister. I have friends with lucrative careers that struggle to pay their mortgages because of the rising interest rates.

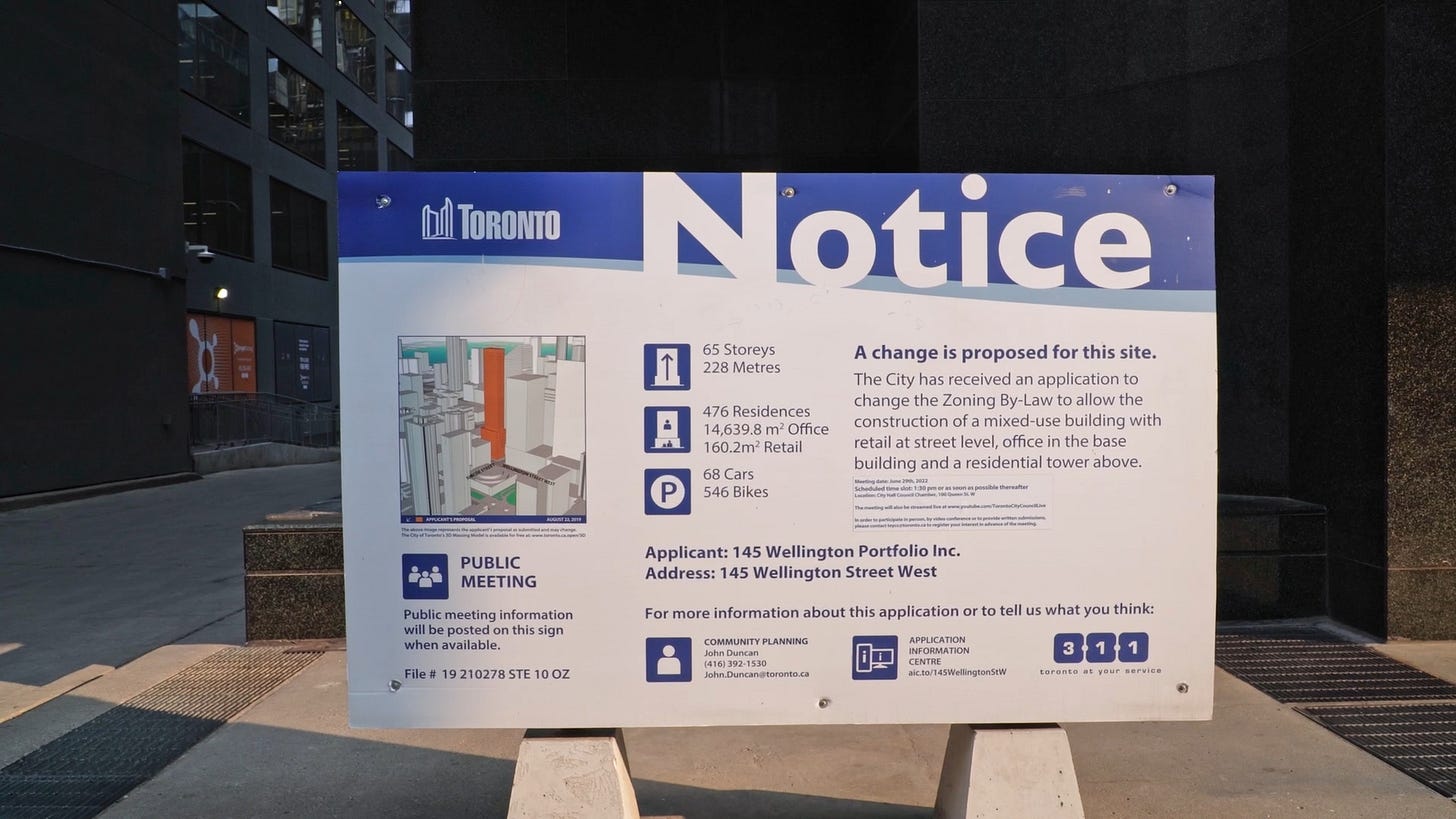

Real estate in Canada confounds even the experts. The news cycle has dubbed this problem the housing crisis. No one knows how to fix the crisis. Some say we need more housing, and there do seem to be a lot of new builds.

I see city notices for condo construction projects across the city. Developers tear down old landmarks to erect glass towers, sometimes they leave the shell of what once was, like a Roman ruin.

Cranes entangle the cityscape like a spider’s web, cutting my dreams of ever escaping. Every day after work, I pass by a condo project on King Street designed by renowned Canadian architect Frank Gehry.

Condominiums are traditionally cheaper than homes, so I wanted to know how much an apartment costs here.

I phoned the number on the showroom door three times. No one answered. The phone just rang and rang endlessly. So I did some digging online, and I discovered a 600-square-foot apartment costs one million dollars.

Old Norse - heimr - world, village

But no matter if I own, rent, or live with my parents, the basic elements of a home stay the same: walls, floors, and ceilings that safeguard me from the world.

To make the space I live in feel more like home, I must leave the safety of inside and journey outside, into the world. This brings me to the second definition Partridge discovered for the word home: the Old Norse, heir, meaning world or village.

The Inglewood Antique Market contains countless items from my village. I’ve visited this store for years, sometimes with an idea of what I want, and at others, bringing nothing with me but a feeling, a desire with no name.

I love this store. The creaking of old wood joists underfoot. The chirping of spring hatchlings in the rafters. And Jon’s warm hello as I enter the front door.

“I'm Jon Medley, owner of Inglewood Antique Market.”

“How long have you had this store,” I asked.

“Well, I've been a dealer here since it opened. I was one of the first dealers here, like 30 years ago. But I took it over about five years ago now.

“There's kind of been a lack of interest in antiques for the last 10 to 15 years. Partially because the older generation that appreciated this stuff and had China cabinets filled with stuff, they're now downsizing, going to condos. They're getting rid of their stuff and the younger generation basically doesn't want China cabinets filled with stuff… They have a different eye.”

Jon is an alchemist specializing in the elements that make up a home: trinkets, tables, chairs. The pieces that arrive in his store are special because they come from other homes in my village. Nothing here is new; I will find no shrink-wrap or cardboard. I do not assemble. I discover, and in that discovery, learn something about myself.

“It's like digging for treasure, really,” Jon said. “That's why some shows, like Storage Wars, are so popular. Because they always go to commercial when they're about to open up a box and they go whoa look at that!

“I hear it when people come in now and they'll go wow look at that and something catches their eye and hearing their response is kind of cool. Even if you don't buy it, you might see something that your grandmother had and it just brings back a memory. You know? A nice memory of being in Grandma's house, or it just brings back feelings. Feelings of home.”

In 2020, I wanted to write the way Don DeLillo writes, and I learned that his technique relied on a typewriter. I found one at Jon’s antique market. I spent years writing slow and tedious drafts on the Smith Corona. Without discovering this typewriter and bringing it back home, One Word would not exist.

But oftentimes, when I’m looking for something, I don’t make the trip to Jon’s store. Instead, I order what I need from Ikea. I admitted this to Jon, and he thought for a few moments, and then said:

“It's because we have to work so hard to be able to afford our mortgages and both couples are working in most cases. You've got to pay for your mortgage; you've got to pay for your car; you have all these overheads.

“A lot of times when you get home, you just wanna relax. You don't want to go out because you're so stressed from that constant barrage of having to work and having to do things. You're a lot more careful with your free time. So if you can do it online in the comfort of your couch when you get home, it's the easy solution for a lot of people. But it's just a shame because a lot of small businesses are going away because of that”

And finally, sitting upstairs, listening to the birds above and the footsteps of shoppers below, he told me what comes to mind when he thinks of home.

“Home is like your safety net,” said Jon. “Home is where, if you get in trouble at school, you get home everything's okay. Mom's there — if you've got a nice home life for sure it makes a difference — but home is that safe ground.

“When you're home, you're comfortable. It's like you're in your mom's womb. That's why the connection to your mom is so strong. I think that that bond never leaves. I think there's an invisible umbilical cord there your entire life, and it's like for me. I kind of associate mom with home.”

Talking with Jon, I found myself imagining a world, not too far into the future, where the increase in the cost of living and ever-shortening of my time means nothing in my home reflects who I am. I have no personal connection to my paintings and desks and lights.

Suddenly, my village is gone. The walls surrounding me are the same walls I see everywhere and the rooms I enter could be anywhere.

Sanskrit - kayati - where he lies down

We’ve arrived at Partridge’s final definition for the word home: the Sanskrit, kayati, which means where he lies down.

I spent some time in a graveyard this month, staring at the headstones and the little gifts left behind for the dead.

Even though it’s where my body will exist the longest, I don’t enjoy thinking about my final resting place. It’s a bad omen, a morbid curiosity. I can’t help but think that talking about coffins and burials shortens my life span, not unlike smoking a cigarette.

But a lack of clarity means it would be up to my family, my wife or my daughter, to take care of the arrangements. Whatever they decided, there’d always be a lingering question: Is this what he would have wanted?

I know this from experience. Ever since my dad passed away, my Mom has held on to his ashes, and he’s followed us from home to home. Right now, he lies down under my mom’s Insignia television.

Until I was working on the word Home, I never thought about my Mom’s responsibility as keeper of Dad’s remains. It’s been over fifteen years, and in many ways, she’s moved on with her life.

We’ve never talked about where he should go, and if we don’t start thinking about it, one day both of my parents will be in bronze containers, and my brother and I will be left carrying them from room to room.

He has to go somewhere, and realizing that my Mom has had him ever since he died, I wondered if things would change if I took him with me. So on a recent visit to Orangeville, I asked her.

“I was wondering if I could take Dad's ashes home,” I said.

“Yeah that's okay,” she replied. “He'd like to go and visit the baby.”

“You've had him for this whole time, right? Sixteen years?”

“Pretty much yeah. You can take him home. I'm fine with that”

Mom and I talked about why we left South Carolina, and she said that it was partly because, even back then, more than a decade before Dad was diagnosed with cancer, he didn’t feel well.

“He was sick and I don't think he really knew how bad,” Mom said. “He just wasn't well, and I think he decided that he better come home. Because we had health insurance down there, but in the end, I think we would have gone through the 2 million deductible pretty fast.”

I spoke to my mom off camera afterwards, and she started to think about where she would want to be buried. I realized that holding onto his ashes means we’re carrying him with us; we haven’t left him behind.

When I returned home, I thought about where to put him. The urn is heavy, so an Ikea floating shelf wasn’t ideal. Dad had spent enough time under a television. But I remember he loved watching movies with his sons, so I decided on the table opposite the TV.

I promised my daughter I’ll always be there when she’s ready to return home. While making this One Word, I realized that’s something my dad promised me.

Reminiscing with Mom, the anger I once held on to those first few years after his death visited me. Couldn’t he have done more to stay alive? Couldn’t he have eaten healthier? Drank less? Seen a doctor sooner?

Sixteen years after his death, and he is here — in the birthday letters, the images, the urn. He kept his promise. By making these videos, I’m trying my best to keep mine.

I may never own a house with land. The small businesses that strengthen villages are dying. And graves are expensive. So I’m building a home for my daughter out of images and music and words. It’ll always be there for her — she can visit anytime she wants — all she has to do is open the door.

Share this post