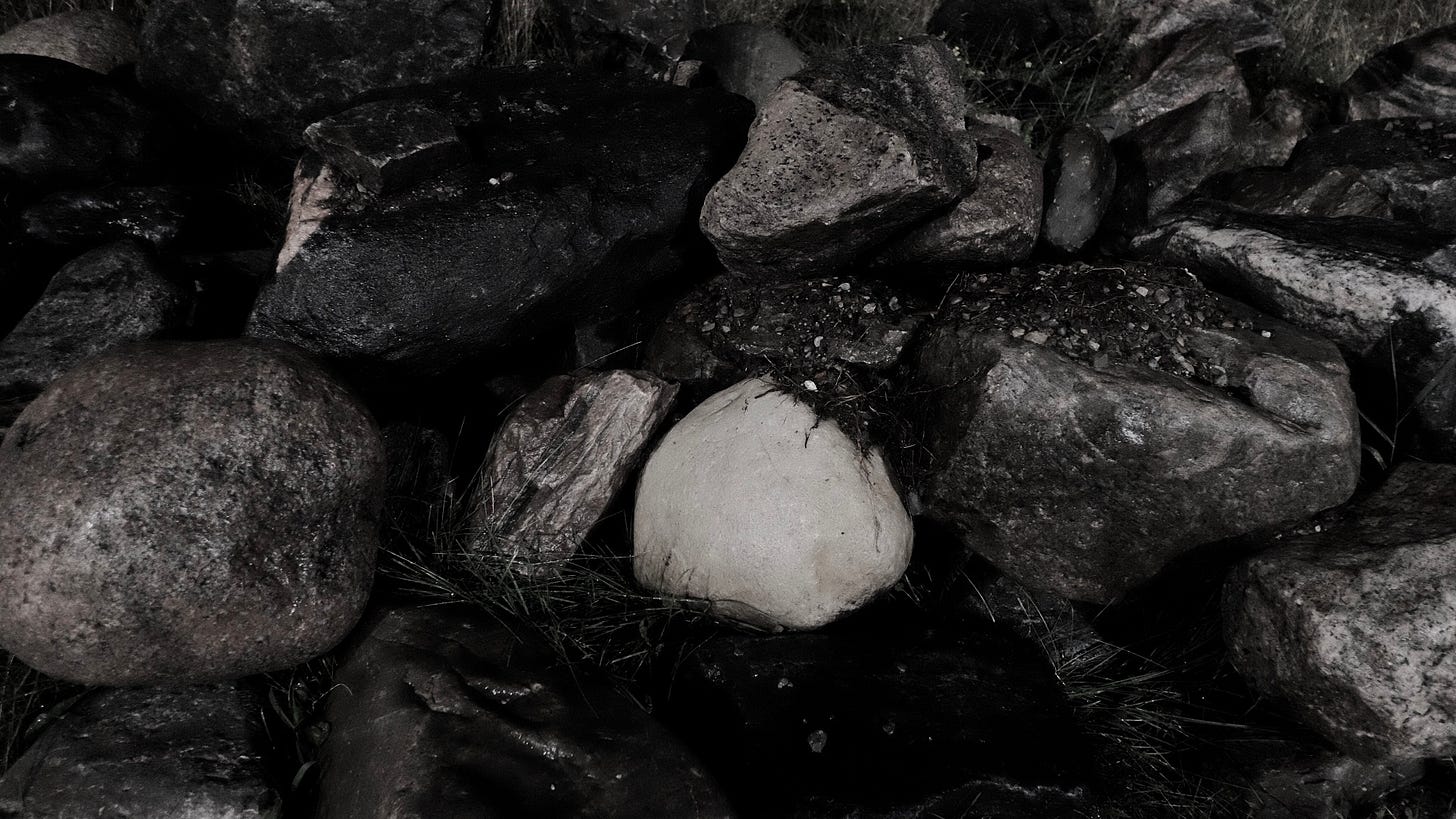

Mossy rocks and river pebbles — the crushed feldspar my neighbours laid in the backyard, white and freckled, and the round-shouldered boulders I can see from my kitchen window.

Then there are the stones that never move, hunkered as they are in the corner of some cornfield I drive by on my way to Home Depot. I’ve never collected rocks or thought much about them as something to want or admire. Maybe as a child, I begged my parents for some fool’s gold or a smooth tiger’s eye.

I sort of remember pulling on my mom’s windbreaker, pointing to something shiny and inert. I put it in my pocket and, later, a day maybe or an hour, I can’t remember, I placed it on a shelf or a box and it stayed there until I forgot about it or, more likely, it rolled away and disappeared.

What are stones?

Chips of the earth’s crust I suppose, which is another way of saying the fingernails of God or the dandruff of a leviathan. Insignificant. Minuscule. Yet part of something timeless and inescapable. The first object a human ever held was probably a stone, and when we pass on to the other side, our loved ones will place above our grave a… you guessed it. Stones are everywhere.

This is more true than you may think. When I was 19, I worked in a gravel pit. It was the summer after my dad died. I don’t remember that winter, just the snow and the bitter cold and this feeling I carried around with me, a feeling of something gone. I stared at the TV and played Mass Effect and gulped down his Lorazepam from September to March. Then, just as the trees were budding and the winds changed, my cousin phoned and asked if I wanted a summer job.

The gravel pit taught me a lot. Of course, I didn’t see it that way at the time. I was spindly and arrogant. I thought myself too smart for the job, and the heavy-machine operators that trundled across the dunes mostly kept their distance. St. Mary’s Cement — that was the gravel company — didn’t much know what to do with me. Being the boss’ relative only added to the confusion.

There were two front-end loader operators, Perry and Jake. Perry had gout real bad and a drinker’s pocked red nose. He hobbled around everywhere and giggled strangely when my mom dropped me off in the mornings. The rumor was he had a gambling problem and a platinum blond wife that practically lived at Mohawk Casino. A cocktail waitress. A pretty one. He wired her money throughout the week to satisfy her slot machine habit. He always said he was broke.

Jake, on the other hand, wore a skull and crossbones bandana and chewed snuff and called women every name he could think of but what they are, which is women. There’s not much else to say about him.

Anyways, back to the stones. I learned that most things are stones because they have stones in them. We may call them by different names, but at the core, they are stones.

For example. Roads are stones. Court houses are stones. Sand is really tiny stone, meaning that concrete, mortar, and glass are stones, too. Gaze upon a cityscape or eight-lane highway, and you are gazing at man’s exhausting relationship with stone.

But there would be no glass tower or road or anything else without gravel pits. A gravel pit transforms raw earth into aggregate material. It’s a place where the basic truths of the world are divided and made specific. They are where dirt becomes three-quarter stone and drainage sand and crushed rock.

There’s also A gravel and B gravel, which undergirds every Canadian road and railway line from St. John’s to Victoria Island. Parking lot asphalt and airport tarmac are — you guessed it — made of stone, too. If we ever build structures on the moon or Mars, well, you get the idea.

I spent my days at the gravel pit driving a rusted Ford pickup around the 100-foot tall man-made piles. I listened to the conveyor belts rattle and the shakers thunder. Part of my job was to ask questions about the stones. Were they the right size? Did they have enough silt content? Would they serve their intended purpose?

“Check the skirt around the pile,” my cousin the dirt scientist told me once as we walked the pit. The sun was high overhead, but I felt the heat rise from under my feet and through my legs. He pointed to the bigger stones that rolled down and rested at the foot of the heaps. “Check them every day and you tell me if you find anything out of the ordinary.”

I nodded. Completely unsure of what he meant.

I conducted stone experiments. I scooped samples into a gallon bucket and brought them to my shack. Sieving the material, shaking them vigorously in a paint mixer, wetting and rinsing them like rice. The goal was to make sure the dirt in question qualified as asphalt sand or plumber’s sand or whatever.

I found it hard to focus. My mind would often wander. This was over twelve years ago. I can’t begin to imagine what this younger version of me contemplated. Probably I just wanted to get home, to sit and watch TV or play a video game. To take some more of my dad’s sleep medication and forget about this job of endless stones.

It was five days a week of staring at rocks. Of sitting in a rundown trailer, slow roasting in the summer heat. Of coming face-to-face with a fundamental question that would take me more than a decade to formulate into words. To bravely write out into an exact sentence.

If my dad, health nut and actual good human, could die of cancer in his 40s, what chance do I have?

I remember waking up one morning that summer and noticing my front teeth were slightly crooked. Were they like that before he died? I couldn’t tell you. It was like I took over a new body, lived in a new world. The dentist said I needed braces and four wisdom teeth extracted. Instead of going to my next appointment, I took more pills.

I had heart palpitations. I had panic attacks. I lost the ability to tell the truth without crying. So I rarely told the truth.

I don’t think anyone at the gravel pit knew what I was going through. Well, that’s not true. My cousin the dirt scientist knew. And Rob.

Right, I can’t tell this story without talking about Rob.

If I’m being honest, I was initially hired to mow the grass and be Rob’s helper. But I rarely mowed the lawn because Rob and I were too busy driving around looking at dirt.

Rob was in his early to mid-thirties. Which, come to think of it, is my age today. Bald-headed, blue-eyed, and quick-witted. He had the build of Odysseus and the vulgar mind of Lil Wayne. Dangerous combo. The type of guy you couldn’t trust with your wallet or your girlfriend because you feared his silver tongue and slippery hands. I liked him. We spent a lot of time together. He talked and I listened.

“You ever sneeze so hard you shit a little?”

Rob did this thing sometimes. When we were driving from one gravel pit to another, skipping down the empty side roads between Creemore and Duntroon, he’d speed up and pretend to hit a goose or mailbox on the side of the road, then veer away at the last second. I’d laugh just to shake off the thrill.

Some people ooze potential like an old car leaks oil. Rob was like that. Everywhere he went I saw the traces of his nature. But it was in the wrong place, mixed up with the dirt and stone.

He’d show up to work with a black eye or busted wrist. His mood could sour like milk in the sun. More than once I caught him staring at the dunes and clenching his fists. I waited in the car, pretending not to notice. But he could also surprise me. This one time, he drove down to the pit weigh station with freshly roasted corned beef and sliced it thick for the guys. They loved him for that.

This other time, Rob picked me up on a Friday morning. He didn’t tell me where we were going and drove to an abandoned gravel pit east of Sunderland. When a gravel pit gets retired, the company will drill down to the water table. A lot of small lakes in Ontario were gravel pits of yore. We fished all day and didn’t catch a thing.

Maybe if he lived in the 16th century he would’ve been a renaissance man; fishing, fighting, fucking. But in 2008, he was an inspector of stones. Rob knew about my loss, and maybe in his way, he understood some of what I was going through.

His dad was an alcoholic, a deadbeat that left his mother with two kids and a defaulted mortgage. So my co-worker was a card-carrying member of the broken home club. That year was my entry into the same club; I see that now. I was raised by two parents that loved one another. Then one of them died, and the loss I carried around like a boulder resembled something of his.

By the end of the summer, my mom had sold the house. Dad’s bottle of Lorazepam dried up and we packed his clothes into boxes. I moved back to the city. The last I heard about Rob was that he joined the army.

Twelve years later, I can only recall the gravel pit in vestiges. And yet, when I stare at the road in front of me or the skyscraper at my back, I’m reminded that after all our efforts to manipulate this world, it’s still mostly stone.

I love this concept. The care, craftsmanship, and what I can only call love that you put into this piece hit me in the face (in the best way). There are so many parts that I loved, but what I found most moving was the way you built up to and segued out of that one sentence about your dad that it took you a decade to formulate. I have to admit this hit me particularly hard, as something similar (though different happened to me) with my mom. Thanks for writing this. I'm very glad to have found your Substack and to catch up on the other One Words ahead of me.

Stones - the ancient foundation of our world, impossible to forget or ignore (in my humble opinion). Thank you for your words about these magnificent beasts!